On paper, Mike Macdonald’s 2025 season reads like a Coach of the Year résumé. In reality, it wasn’t enough.

Despite guiding the Seattle Seahawks from a 9–8 non-playoff team just two years ago to a 14–3 record and a Super Bowl LX appearance, Macdonald finished a stunning third in the AP NFL Coach of the Year voting. Not second. Third.

And that’s where the discomfort starts.

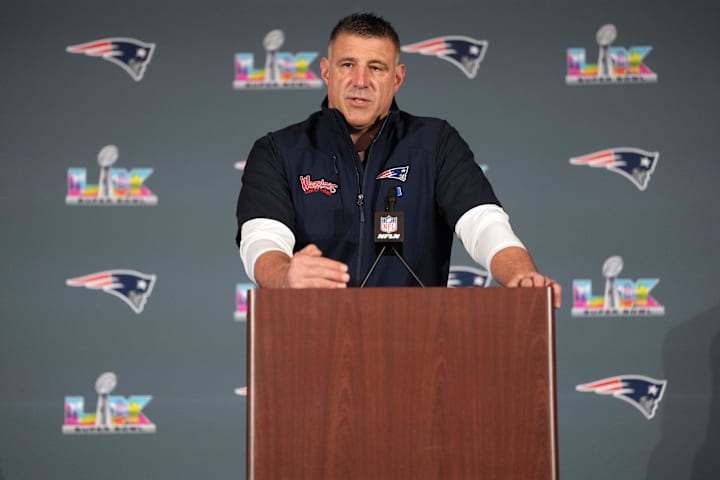

The award ultimately went to New England Patriots head coach Mike Vrabel, who engineered a similarly dramatic turnaround in his first year back as a head coach. Vrabel took a Patriots team coming off back-to-back 4–13 seasons and transformed it into a 14–3 juggernaut, earning his second Coach of the Year honor.

It’s a compelling story. Fired. Reset. Redemption.

But it wasn’t the only one.

What makes Macdonald’s placement so jarring isn’t just that he didn’t win — it’s that he was leapfrogged by Jacksonville Jaguars head coach Liam Coen, who finished second despite falling in the Wild Card round. Coen, like Vrabel, inherited a 4–13 team and led Jacksonville to a 13–4 record and an AFC South title.

Strong season. No doubt.

But Macdonald is still playing.

The Seahawks’ turnaround didn’t happen against a soft backdrop, either. Seattle faced the 15th-hardest strength of schedule in the league (.498), compared to New England’s league-easiest (.391) and Jacksonville’s middling .425. Those numbers don’t tell the whole story — but they add context the voting results seem to gloss over.

The voting breakdown made the gap even clearer. Vrabel received 19 first-place votes and 302 total points. Coen followed with 16 first-place votes and 239 points. Macdonald earned eight first-place votes and finished with 191 points — a respectable showing, but one that quietly acknowledged him without fully embracing his case.

That silence is what lingers.

Macdonald didn’t campaign. He didn’t sell a narrative. He simply coached — and won. His Seahawks didn’t just improve; they evolved. From structure to discipline to identity, Seattle looked like a team built with intention rather than momentum.

And yet, the award conversation drifted elsewhere.

Perhaps the story voters gravitated toward wasn’t about the hardest climb, but the most dramatic reset. Or maybe it was about familiarity — Vrabel’s return to prominence, Coen’s first-year splash. Macdonald’s rise, by contrast, felt steadier. Less theatrical. Harder to compress into a headline.

Ironically, that may be why it mattered less in a vote.

Chicago Bears coach Ben Johnson and San Francisco’s Kyle Shanahan rounded out the finalists, each collecting first-place votes but finishing behind Macdonald. Even that detail underscores how fractured the conversation became — no consensus beyond the winner, no clear agreement on what should matter most.

Now comes the quiet twist.

Macdonald still has a chance to claim the only piece of hardware that truly endures. On Sunday, he’ll face Vrabel head-to-head in Super Bowl LX, with the Lombardi Trophy on the line. One coach will validate a season with silverware. The other will be left with accolades.

And history has a way of remembering one more clearly than the other.

Coach of the Year honors capture moments. Championships capture eras.

Macdonald may not have won the vote. But if Seattle wins Sunday, the debate won’t just reopen — it will flip.

And suddenly, finishing third might feel like the least important result of all.

Leave a Reply