Matt Nagy hasn’t called a single play for the New York Giants yet. Training camp is months away. The playbook isn’t public. And still, the criticism has already arrived.

That’s how heavy the Chiefs’ shadow is.

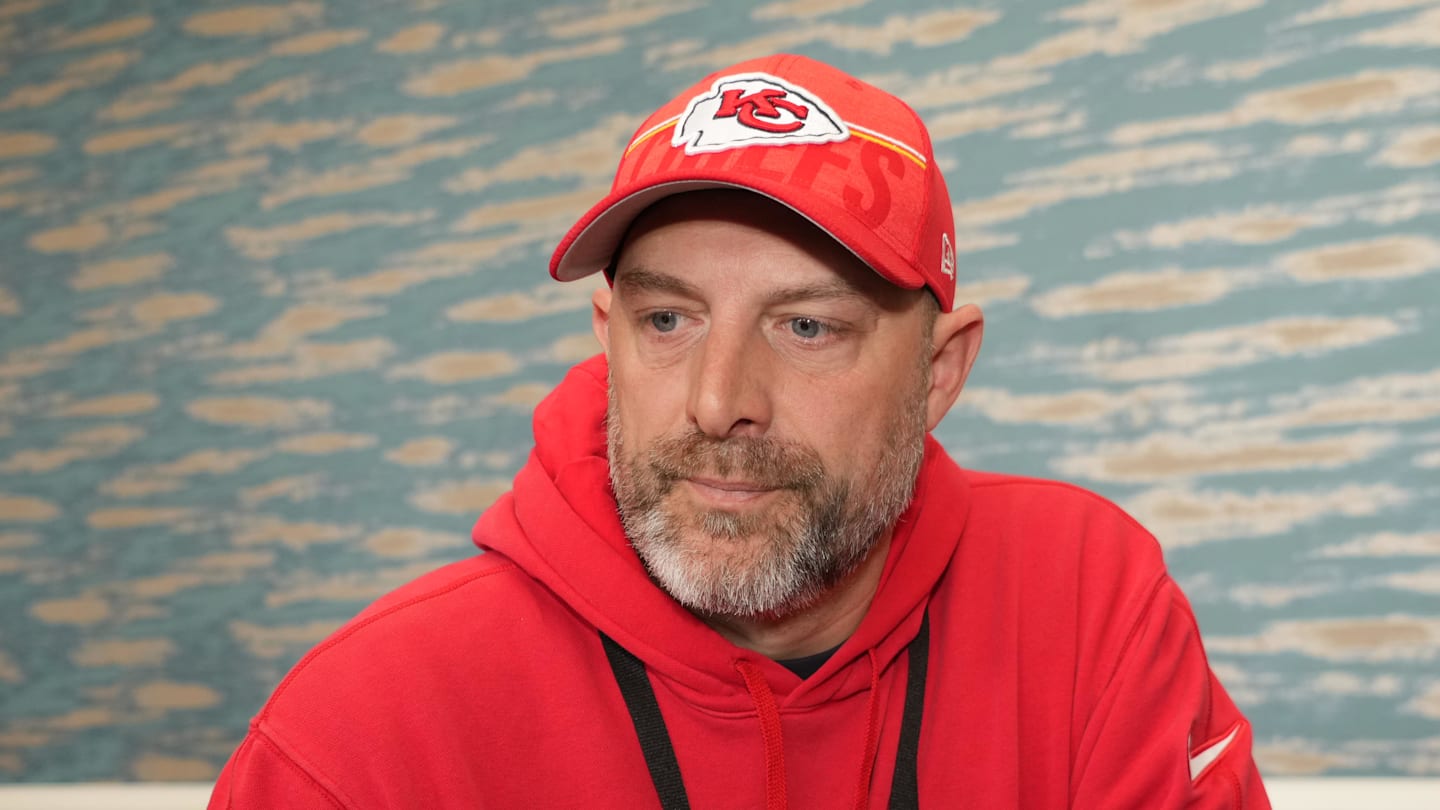

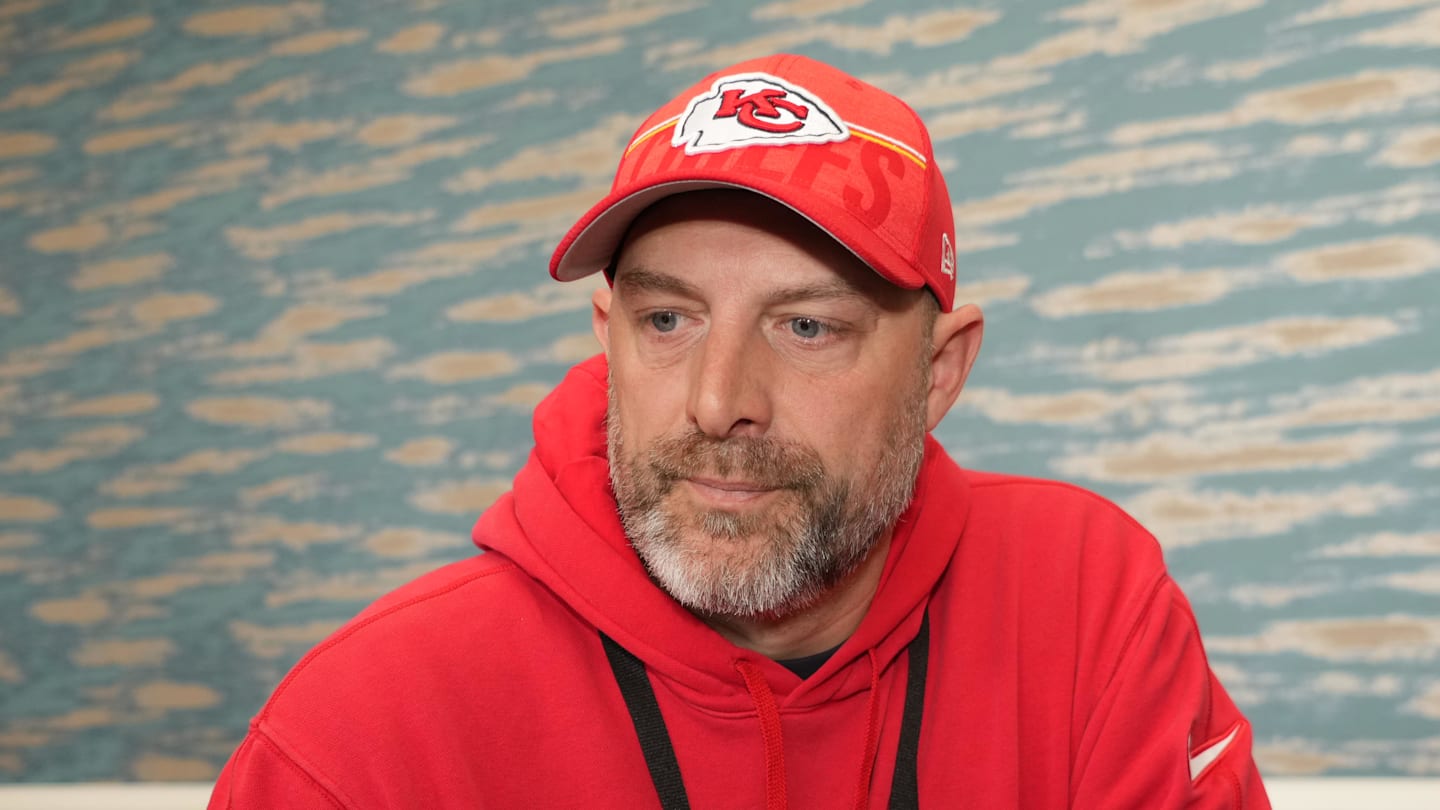

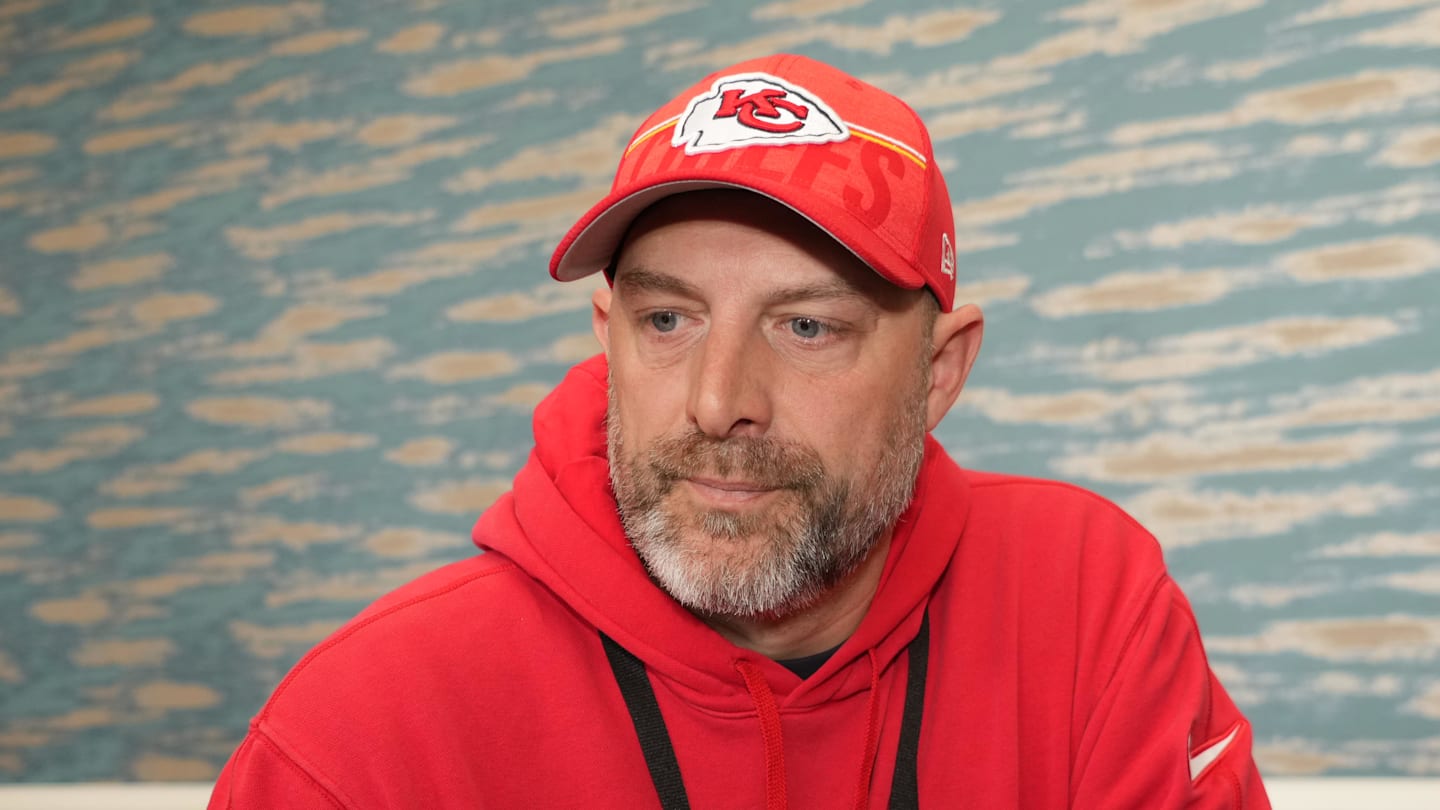

When John Harbaugh tapped Nagy as the offensive coordinator for his first Giants staff, the move was framed as a reunion-by-proxy. Andy Reid’s influence loomed large, and Nagy’s familiarity with quarterback-friendly systems made the hire feel safe—on paper.

But during Super Bowl LX media week, ESPN analyst Mina Kimes quietly reframed the conversation. And Giants fans noticed.

“RPO is going to be a big part of that offense,” Kimes said. “It was a big part in Kansas City. It’ll be a big part in New York.”

That statement alone wasn’t alarming. The problem came next.

Kansas City didn’t just use run-pass options. They leaned on them—hard. According to league tracking, the Chiefs called RPOs on 14.3 percent of their plays, the highest rate in the NFL. And when Patrick Mahomes was at the controls, over 92 percent of those RPOs turned into passes.

Defenses adjusted. Quickly.

What once created hesitation began creating anticipation. Opponents stopped respecting the run element altogether. By the fourth quarter, Kansas City’s offense wasn’t deceptive—it was readable.

That predictability mattered.

The Chiefs struggled to overcome late deficits the way they once did. Drives stalled. Balance disappeared. And the run game became more of a suggestion than a threat.

Now, Giants fans are wondering if that same blueprint is headed to New York.

Kimes didn’t mince words. She emphasized that the Giants cannot operate the same way. With a dual-threat quarterback like Jaxson Dart and a backfield built to absorb contact, New York’s offense should lean into physicality. Not as an archaic philosophy—but as a structural foundation.

In Kansas City, the run game stemmed from the pass. In New York, Kimes argued, it needs to be the opposite.

That’s the challenge Nagy faces.

Because the Chiefs’ issues weren’t theoretical. They were measurable. Kansas City averaged just 2.7 yards after contact per carry—tied for worst in the league.

Outside of short-yardage situations, explosive runs were nearly nonexistent. According to NFL.com, the Chiefs produced only six runs of 10-plus yards over expectation all season.

That wasn’t bad luck. It was design catching up to itself.

The irony is sharp: Kansas City now needs to fix the exact problem New York is worried about inheriting.

Nagy, calling his own plays again, won’t have the insulation of Mahomes’ improvisational brilliance to bail him out. The Giants’ margin for error is thinner. Predictability won’t just stall drives—it could stall development.

None of this means Nagy is destined to fail. But it does mean his reputation arrives with baggage. And not the kind you can shrug off with preseason optimism.

The Giants didn’t hire Nagy to recreate Kansas City. They hired him to adapt what worked—and discard what didn’t.

The problem is, everyone watching knows exactly what didn’t.

And until Nagy proves otherwise, every RPO, every stalled run, and every predictable sequence will feel less like growing pains—and more like déjà vu.

Sometimes, the harshest criticism isn’t about what you might do.

It’s about what you already did—and whether you learned from it.

Leave a Reply