The Phillies didn’t lose Bo Bichette because they were cheap.

New York Mets v Philadelphia Phillies | Tim Nwachukwu/GettyImages

They lost him because the market changed—and Philadelphia didn’t.

This offseason has been harder to swallow than most in recent memory. The Phillies believed they had a deal in place to land Bichette, a shortstop who could have reshaped their infield and extended their championship window.

Reports suggested Philadelphia offered seven years and $200 million—a number that would’ve felt massive in any previous era of free agency.

Then the Mets stepped in late and flipped the table.

Bichette chose New York on a short-term deal with a staggering annual value, the kind of contract that makes even a $200 million offer feel strangely outdated. It wasn’t just a gut punch. It was a signal that the Phillies’ entire free-agent strategy may now be fighting the wrong war.

Because the league’s biggest stars aren’t chasing total dollars the way they used to.

They’re chasing leverage.

And leverage lives in shorter deals, higher AAV, and opt-outs that keep the player in control.

That’s exactly what happened this winter. Bichette reportedly landed around $42 million per year. Kyle Tucker went even higher, reaching a jaw-dropping $60 million annual salary on a short-term structure.

The Dodgers and Mets didn’t just outbid teams—they outmaneuvered them with a new kind of offer: immediate money, maximum flexibility, and the promise that the player never has to feel trapped.

The Phillies, historically, hate that.

For years, their approach has been consistent: lock up stars long-term, keep the annual value manageable, avoid opt-outs, and build around a stable core.

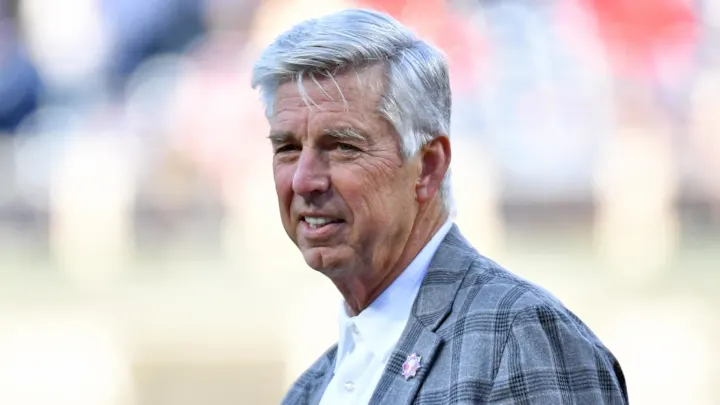

Under managing partner John Middleton and president of baseball operations Dave Dombrowski, Philadelphia has committed enormous money—just distributed differently.

Bryce Harper: 13 years, $330 million

Trea Turner: 11 years, $300 million

Aaron Nola: 7 years, $172 million

Kyle Schwarber: 5 years, $150 million

Those deals aren’t small. They’re massive. But they’re built to protect the team as much as they reward the player. Spread the cost.

Reduce the annual hit. Maintain long-term roster planning. Avoid the nightmare scenario of a player opting out right when you need them most.

The problem is: stars are starting to prefer the nightmare scenario.

Because it’s not a nightmare for them.

It’s power.

And in a market where the Mets and Dodgers are willing to spend absurd amounts of immediate money, the Phillies’ traditional approach suddenly feels like it belongs to a different era. Even when Philadelphia puts a giant number on the table, it can still lose—because the structure isn’t what elite players want anymore.

That’s where the overlooked payroll reality becomes crucial.

The Phillies are about to get flexibility in a way they haven’t had in years.

After re-signing J.T. Realmuto, FanGraphs projects the Phillies’ 2026 luxury tax payroll to be just over $317 million. But their estimated 2027 payroll sits around $202 million.

That’s roughly $115 million coming off the books after the 2026 season.

A massive shift. The kind that changes what a front office can realistically do—if it’s willing to adjust its mindset.

Yes, there will be holes to fill. There always are when money clears. But this isn’t just about replacing players. It’s about finally having the financial oxygen to chase the new type of superstar contract: short-term, high AAV, opt-outs included.

It’s uncomfortable for Philadelphia.

It’s not how they’ve operated.

But it may be the only way forward.

The Phillies don’t like opt-outs, but they may have to stop treating them like poison. Because opt-outs are now part of the recruiting pitch. They’re part of the trust signal. They tell a star: “We want you, but we won’t trap you.”

And here’s the part Phillies fans may not want to admit:

Bo Bichette could be back on the market soon anyway.

If his deal includes opt-outs—as expected—he could become available again next offseason. And if the Phillies enter that moment still trying to win with total dollars instead of annual impact, they could watch the same story repeat itself.

Philadelphia doesn’t need to abandon long-term planning entirely. But they do need to stop pretending the market will return to what it was.

The new market rewards aggression, flexibility, and risk tolerance.

And if the Phillies truly want to win the World Series—not just contend, not just “stay competitive,” but actually finish the job—they may have to accept something that feels almost heretical in their recent history:

Sometimes the best way to keep a star…

is to give them a way out.

Leave a Reply