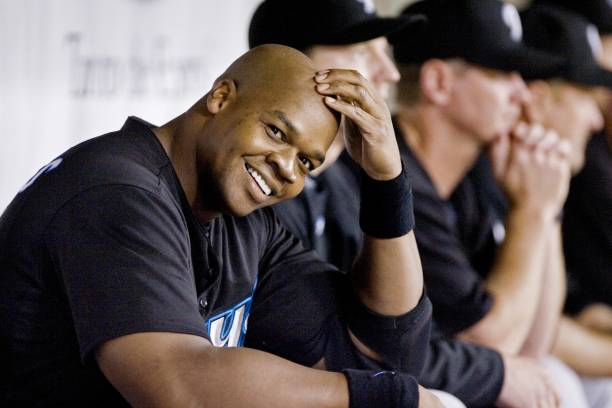

Frank Thomas didn’t write a long statement.

He didn’t schedule an interview.

He didn’t explain his pain.

He wrote one sentence.

And that was enough to stop people mid-scroll.

When the Chicago White Sox posted a Black History Month graphic on X, intended to honor “momentous firsts” in franchise history, Thomas noticed something missing — himself.

The player who holds nearly every meaningful offensive record in team history. The face of an era. The man whose performance helped build both relevance and revenue.

“I guess the black player who made you rich over there and holds all your records is forgettable!” Thomas replied. “Don’t worry I’m taking receipts!”

The reaction was immediate. Some called it petty. Others called it overdue. But what lingered wasn’t the tone — it was the truth embedded inside the frustration.

Frank Thomas wasn’t upset about a graphic.

He was reacting to erasure.

The White Sox chose to frame Black History Month through “firsts,” spotlighting Dick Allen’s 1972 MVP season. Allen deserved that recognition.

No one disputes that. But the absence of Thomas — a two-time MVP, Hall of Famer, and the statistical backbone of the franchise for over a decade — felt conspicuous.

Especially to him.

Thomas’ relationship with the White Sox has always been complicated. His playing career there ended not with a celebration, but with conflict.

After leaving the team following the 2005 season, he clashed publicly with management and later sued the organization over a misdiagnosed foot injury — a lawsuit that wouldn’t be settled until 2011.

Even after that, he returned in a consulting role, attempting reconciliation. From the outside, it appeared the wounds had healed.

This moment suggests they never fully did.

What makes Thomas’ reaction resonate is timing. Black History Month is not about nostalgia.

t’s about acknowledgment. About choosing whose stories are elevated, and whose contributions are treated as assumed, permanent, and therefore optional.

Thomas’ records are still there. His name still sits atop leaderboards. But institutional memory isn’t just about numbers — it’s about narrative.

And narratives are curated.

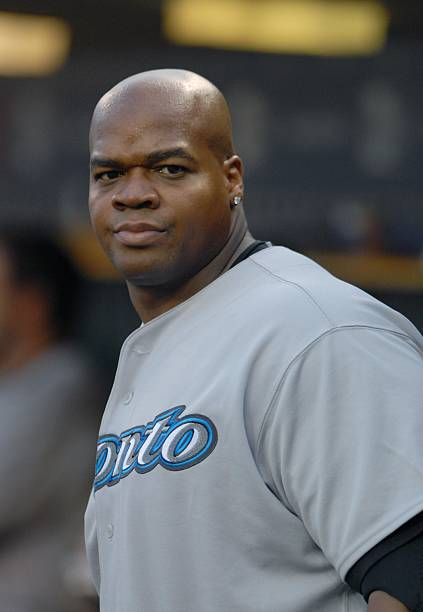

Ironically, the Toronto Blue Jays — the team Thomas briefly played for late in his career — included him in their Black History Month graphic. The same player released by Toronto after one season was still deemed worthy of mention. The team where he holds no records remembered him. The one where he holds all of them did not.

That contrast sharpened the moment.

This wasn’t a scandal. No policies were broken. No statements required retraction. And yet, it revealed something uncomfortable: how easily greatness can be normalized into invisibility.

Thomas didn’t demand an apology. He didn’t accuse anyone of malice. He simply pointed out what was missing — and let the implication do the work.

That’s why the response hit so hard.

Because it forced fans, executives, and media alike to confront a difficult question: when history is selectively framed, who decides which legends still count?

Frank Thomas didn’t ask to be celebrated.

He asked not to be forgotten.

And in a sport that constantly measures legacy, that distinction matters more than any graphic ever could.

Leave a Reply