Imagine you’re missing. Not just lost, but vanished. And then, eight years later, they find you. Not in the woods, not at the bottom of a lake, but in an abandoned mine, sealed from the inside. You’re sitting, leaning against the wall, next to your loved one. You look like you’ve simply fallen asleep, but you’re dead, your legs broken. This isn’t a movie monster story.

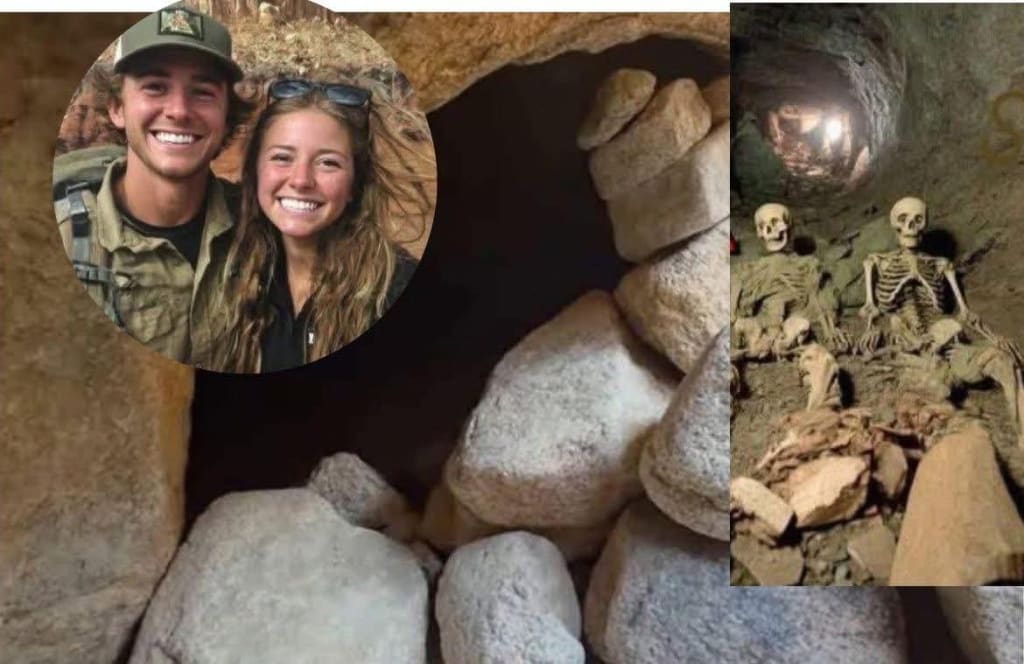

This is the true story of Sarah and Andrew. It’s the story of how a three-day trip to the desert turned into an eight-year mystery, the answer to which turned out to be more terrifying than anyone could have imagined. This story began in 2011. Sarah and Andrew were an ordinary couple from Colorado. She was 26. He was 28. They weren’t extreme sports fans or survival experts. They were simply two people who loved each other and wanted to spend a weekend away from the city.

Their plan was simple enough. Take their old but reliable car, drive to the desert lands of Utah, camp there for three days and two nights, photograph the landscape, and just be together. They chose a specific location, not far from an area where uranium was actively mined in the mid-19th century. Now all that remains are abandoned mines, rusted equipment, and roads that disappeared from official maps long ago. For them, it was simply exotic, a chance to see something unusual and take unique photos.

They weren’t looking for adventure, much less trouble. Before leaving on Friday morning, Sarah texted her sister: “We’re leaving. We’ll be back Sunday night. I love you.” That was the last message their loved ones received. They packed water, food, a tent, sleeping bags, the usual tourist gear. They didn’t bring any special equipment for exploring mines or anything like that, because they had no intention of doing so. They were only interested in the surface, only the views of the desert at sunset.

The weekend passed. Sunday night arrived. Sarah and Andrew didn’t return. At first, no one panicked. Well, maybe they were delayed. Maybe there was a bad signal somewhere. These things happen. But when they both didn’t show up for work on Monday, their families raised the alarm. Calls to their phones immediately went to voicemail. Friends they’d been in touch with confirmed they had gone to Utah, to the old mining area. The family immediately contacted the police, and a search operation was organized that same day.

At first, everyone had hope. Police, volunteers, and dozens of people combed the area. The Utah desert is a vast, almost endless space. Canyons, rocks, dry riverbeds. Finding two people here is like looking for a needle in a haystack. Searchers in cars and off-road vehicles scoured all known and abandoned roads. A helicopter hovered over the area for hours, trying to find any sign. A car, a tent, a campfire. But the days passed, and there were no clues.

None at all. No one had seen their car. No one had ever encountered a couple like them. It was as if they had vanished into thin air the moment they left their city. Hope faded with each passing day. The desert climate is unforgiving. During the day, the heat was unbearable, and at night, it was cold. If they ran out of water or simply got lost, their chances of survival diminished by the hour.

The police began to consider other possibilities. Perhaps they never made it to Utah. Perhaps they decided to run away and start a new life. But this theory was quickly dismissed. Their bank accounts were intact. Their credit cards were intact. They had left their pets at home and asked a neighbor to watch them. People planning to disappear forever. Don’t do that. The criminal theory also seemed unlikely. There were hardly any people in the area.

It was in the middle of nowhere. The probability of a random attack was extremely low. The search continued for almost a week. The volunteers and family members didn’t give up, but the police were already preparing to end the active phase of the operation. And then, on the seventh day, when all hope had almost vanished, a helicopter pilot noticed a flash in the sun. It wasn’t just a flash. It was flashing lights. They found Sarah and Andrew’s car.

It was parked on one of those abandoned roads that were barely visible from the ground. The road led to old uranium mines and ended a few kilometers away. The car was in the middle of the road as if it had just been abandoned. The first thing that caught the attention of the group that arrived at the scene were the hazard lights. The battery was almost dead and the lights were flickering dimly. It was strange. Hazard lights come on when there’s a breakdown or a stop.

This meant that, when the car stopped, Sarah and Andrew were next to it. The police inspected the car. There were no signs of theft or accidental damage. The doors were open. Inside, everything seemed to indicate the owners had been gone for a couple of minutes. There was a map of the area on the passenger seat, next to an empty water bottle. Andrew’s phone was found in the glove compartment. Forensic experts later confirmed that he had no missed calls, and no attempts were made to call the emergency services or anyone nearby.

The battery was more than half charged. But the most important find was the navigation system. It was turned on, and the screen showed a route leading along this deserted road to one of the old mines. This discovery gave hope and raised even more questions. Why didn’t they call? Perhaps there was simply no cell phone service in the area, and they knew it. But then, why was the car abandoned? The police checked the tank. It was completely empty.

That explained why they had stopped. They had simply run out of gas. They turned on their hazard lights to be visible. It made sense. But where did they go next? And why did the navigator point out a specific mine? Perhaps they hoped to find help there or shelter from the sun. The search team, encouraged by the discovery, immediately set off along the route indicated by the navigator. They walked along a barely visible, sun-baked path.

There was not a soul around, only the wind and the resonant silence of the desert. After a couple of kilometers, they reached their destination. It was the entrance to an old uranium mine. An ordinary descent into the rock, littered with rusty scrap metal and old planks. The entrance was narrow, but a person could pass through. The searchers cautiously examined everything around them, but found nothing. No tracks, no belongings, no signs that anyone had been there recently.

The wind and sand of the past few days could have hidden any traces. Rescuers shouted his name several times in the darkness of the mine, but there was only silence. Going deeper without special equipment was deadly dangerous. Old mines are labyrinths where a collapse can occur at any moment or the buildup of gases can poison you. A search of the surrounding area also yielded no results. They combed every meter within a radius of several kilometers from the car to the mine entrance.

No tents, no sleeping bags, no campfire, nothing at all. It was inexplicable. If they had run out of gas, the logical thing to do would have been to camp next to the car and wait for help. Or if they had gone looking for it, they would have taken at least some things, like water. But all their basic equipment—the tent, sleeping bags, and food—had simply vanished, just like Sarah and Andrew. After this discovery, the active search continued for several more days, but without success.

The police couldn’t send people into the depths of the unstable mine without direct evidence that the couple was inside. It would have been an unjustified risk. Gradually, the search operation wound down. Sarah and Andrew’s case was classified as missing. Their photos were posted on bulletin boards and written about in local newspapers. Their families hired private investigators, but even they couldn’t find new leads. Months passed, then years. Sarah and Andrew’s story became one of those dark legends told around the campfire.

A mystery covered in desert dust. It seemed no one would ever know what had happened to them. The car with an empty tank and the navigator pointing to a dark hole in the rock were the only silent witnesses to their final journey. And for eight long years, absolute silence reigned in this case. Eight years have passed. For most, Sarah and Andrew’s story has become just another unsolved mystery, a sad reminder of how dangerous nature can be.

The families continued to live with an open wound, without answers and without even the chance to bury their loved ones. The case was forgotten in the archives under the label “cold.” And it would have remained that way if not for two neighbors who, in 2019, decided to earn some extra money collecting scrap metal. These men weren’t detectives or adventurers. They simply knew there was a lot of abandoned equipment in the area of the old uranium mines that could be scrapped and sold.

One hot autumn day, they drove their old pickup truck along the same forgotten roads where they had once found the missing couple’s car. Their destination was the same mine Andrew’s navigator had pointed out. Not because they knew this detail, but simply because it was a large deposit where they expected to find a lot of metal. When they reached the entrance, they saw the same thing the searchers had seen eight years earlier: a hole in the rock filled with debris.

But something was wrong. The entrance, which had previously been simply littered with junk, now seemed sealed. Someone had dragged a large, rusty sheet of thick metal there and somehow secured it by piling stones and beams on top. It was strange. Normally, mines are left open or sealed with concrete and warning signs. It looked as if someone, hastily but very confidently, had tried to hide something or prevent anyone from entering. For the metal prospectors, this sheet itself was a prey.

They brought a gas cutter with them. They spent several hours in the heat cutting a passage in the sheeting large enough to crawl through. When they finally finished, the opening emitted stale, cold, and completely motionless air. The kind of air that only exists in places that have been sealed for many years. One of the men pointed a powerful flashlight inside. At first, the beam revealed only bare stone walls covered in dust and a floor strewn with small stones.

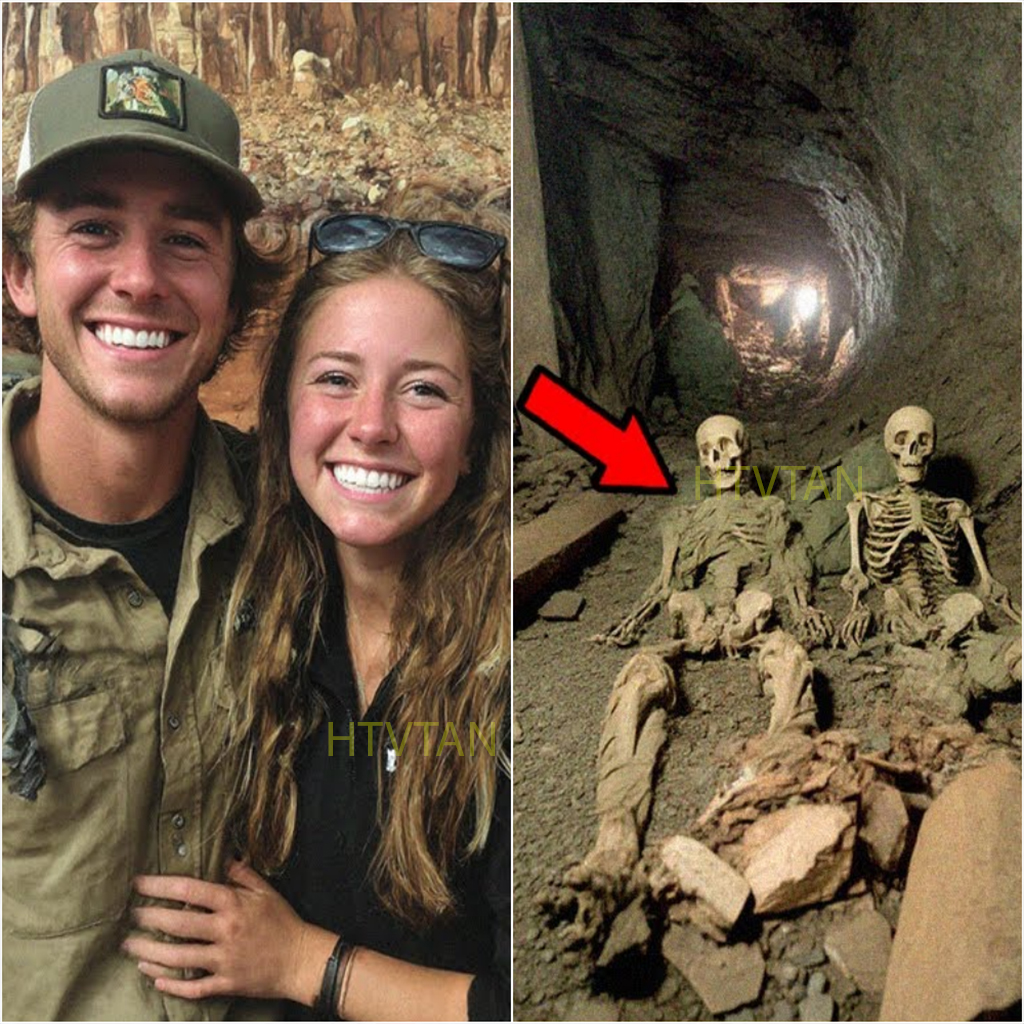

The shaft plunged directly into the rock. He shone the beam of light forward, peering into the darkness, and then the light went out. At the end of this small first chamber, about 15 meters from the entrance, were two figures. They were sitting on the floor, their backs against the wall and their heads slightly bowed. They were very close to each other. The man with the flashlight didn’t understand what he was seeing at first. Perhaps they were mannequins or some kind of trash that, from a distance, looked like people.

He called his partner. His partner also looked inside and froze. They both stared silently into the darkness, and then one of them said quietly, “Those are people. There was no panic, just commotion. The poses were too peaceful.” There was no blood, no signs of a struggle, just two people who seemed to have sat down to rest in the fresh air and fallen asleep. But they both understood that people don’t sleep in a sealed mine. They immediately drove several kilometers until they found a cell phone signal and called the police.

The news of the discovery in the old mine shocked the entire state. The police officers who worked on Sarah and Andrews’ case eight years ago immediately understood what place they were referring to. An investigation team and forensic experts were dispatched to the scene. Working inside was difficult. The air was stale, and the silence inside was oppressive. The scene they saw was exactly as the metal detectorists had described it: two people, a man and a woman, sitting, leaning against a wall.

Their clothing, ordinary hiking clothes, was weathered but not torn. There were no personal belongings around them—no backpacks, no water, nothing. Just bare rock and dust. The bodies were heavily mummified due to the mine’s dry air, which had preserved them in that position. Sarah and Andrew’s families were informed of the horrific discovery, and soon DNA analysis confirmed what everyone already knew: it was them. The eight-year search was over. The mystery of their whereabouts was solved.

But from that moment on, a new, even more terrifying mystery began. What had happened to them inside the mine? The investigation began with a detailed examination of the scene and the bodies, and a series of oddities immediately emerged that didn’t fit any logical explanation. First, there were no injuries on the bodies or clothing that would indicate an attack. No cuts, no gunshot wounds, no signs of a struggle. Second, the scene itself. They were sitting calmly. They didn’t appear panicked, trying to get out, or calling for help.

They were sitting there. But the most important and shocking fact was established by the medical examiner during the autopsy. Both Sarah and Andrew had leg fractures, multiple fractures in the shins and feet. These were serious injuries that could not have occurred on their own. These types of injuries occur when falling from a great height. But how did this fit with the lack of other injuries and their calm posture? And then the investigators turned their attention to the structure of the mine itself.

The passageway the metal hunters had opened was horizontal, but above where Sarah and Andrew were sitting, there was another hole in the ceiling, a vertical shaft ascending to the surface. A new version began to emerge, and it was terrifying. Sarah and Andrew didn’t enter the mine through the side entrance. They fell into it. They fell down the same vertical shaft, possibly hidden by bushes or planks on the surface. They flew several meters and landed on the stone floor, breaking their legs.

They were alive, but immobilized. They couldn’t get up or go anywhere. They were trapped. But this version only explained the injuries. It didn’t explain the main point: Who sealed the side exit and why? Investigators carefully examined the metal sheet that sealed the entrance. The examination showed it was welded to the rock with a professional welding machine. Furthermore, the welding method indicated it had been done from the inside. However, no equipment was found inside the mine.

No welding machine, no generator, not even a simple hammer, nothing. It was impossible. Someone had entered the mine, welded the only exit from the inside, and then simply disappeared, leaving no tools behind. The lack of any signs of a struggle now seemed even more sinister. If they had been attacked, they would have defended themselves. But if they had fallen and broken their legs, they would have been completely defenseless. Anyone who had found them in that state could have done anything to them.

And someone did. Someone found them injured and helpless. And instead of helping them, that someone decided to bury them alive. They dragged a sheet of metal to the side exit, welded it shut, condemning Sarah and Andrew to a slow death in complete darkness from hunger and thirst. The idea was so monstrous it was hard to believe. This wasn’t negligence or an accident. It was a cold-blooded, cruel murder that lasted for days. The police realized they weren’t looking for just any criminal.

They were looking for someone who knew the area well. Someone who knew about the existence of this mine, the vertical descent, and the side exit. Perhaps he himself had set the trap on the surface where they had fallen. And he knew how to hide his tracks and go undetected. Perhaps through some narrow crevice or ventilation shaft that only he knew about. The case went from being an unsolved case to a top-priority investigation. Now, the police aimed to find the monster who had turned the old mine into a grave for two innocent people.

And this monster was still out there somewhere. The police worked on the case for two years. The list of suspects was very short. Who could possibly know so much about these mines? Who could possibly have welding equipment and the skills to use it in such a remote area? Investigators began doing what they should have done in 2011. They began digging up all the ownership and leasing records for these abandoned lands. Most of the mines don’t belong to anyone, but some plots, including the one where Sarah and Andrew died, were leased long-term to a private individual.

He was a man in his sixties who lived alone on a small ranch a few dozen miles away. He had leased the land for many years, ostensibly for geological research, although he didn’t actually conduct any real activities there. Neighbors described him as unsociable and reserved, who didn’t like anyone appearing on his property. He had had frequent conflicts with tourists or hunters who accidentally invaded his land. For the police, this was the first real lead they had in all their time.

They obtained a search warrant for his house and property. The man, the owner of the rented property, greeted the police without surprise, but with ill-disguised hostility. He denied everything, claiming to have known nothing about the missing tourists and that he hadn’t been in the mine area for many years. But during a search of his workshop, investigators found something that silenced him. Hanging from a nail among a pile of old tools was a bunch of keys.

These were the keys to the old locks on the doors that blocked some of the mine entrances. And in a desk drawer, under a pile of old bills, lay a yellowed sheet of paper rolled into a tube. It wasn’t just a map of the area. It was a detailed diagram of the internal passageways of several mines, including this one. The diagram marked not only the main entrance and the vertical shaft, but also several narrow ventilation tunnels that even the mine’s supervisory service didn’t know about.

One of these tunnels led to the surface, almost a mile from the main entrance. This was the answer to the question of how the killer could have disappeared after sealing the exit from the inside. It had its own secret exit. When shown this diagram, the man realized it was useless to deny it and spoke, but not out of remorse. He told his version of events with dryness and detachment. That day, he was patrolling his territory and heard screams.

He followed the sound and found two people in the mine. They had fallen into an old shaft he had covered with rotten boards to keep out animals. He saw that they were alive, but injured. They were on his land. Strangers, intruders. In his twisted mind, they weren’t victims, but a problem. He didn’t speak to them. He just walked away silently. He returned to his ranch, grabbed a welding machine and a generator, loaded everything into his pickup truck, and drove to the side entrance of the mine.

He didn’t see himself as killing them. In his logic, he was simply securing his property. He welded the exit so that outsiders could no longer enter where they shouldn’t. He admitted to blocking the entrance, but denied murder to the very end, insisting they were guilty of trespassing on his property. He simply closed the gate behind the intruders. The fact that two wounded men died in the darkness and agony behind that door didn’t seem to bother him.

The trial wasn’t long. There was more than enough evidence. The prosecution didn’t directly charge him with intentional homicide. It was difficult to prove he had wanted her dead. The official version, as recorded in the verdict, was: intentional abandonment of a man in danger, resulting in the death of two people. He found Sarah and Andrew injured, and instead of helping them, he condemned them to a painful death by enclosing them in a stone bag. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

The mystery that had tormented everyone for nearly ten years was solved. Behind this terrible and inexplicable disappearance were neither mystical desert forces nor serial killers from the movies. There was only one person, one person whose paranoid hatred of strangers proved stronger than common human compassion. Sarah and Andrew’s story ended, not on the day they disappeared, nor even on the day their bodies were found. It ended the moment Justice named the person who left them to die in the cold darkness of an abandoned mine.

Leave a Reply