Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites are falling out of orbit, raining down toxic metals and threatening the ozone layer, raising fears of a space disaster.

SpaceX’s Starlink low-orbit internet satellites are falling out of orbit at an increasingly alarming rate: currently, one to two satellites are re-entering Earth’s atmosphere every day. That number will continue to rise as more satellites reach the end of their lives and the number of low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations continues to explode, according to astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Space and Space. Design is one of the reasons.

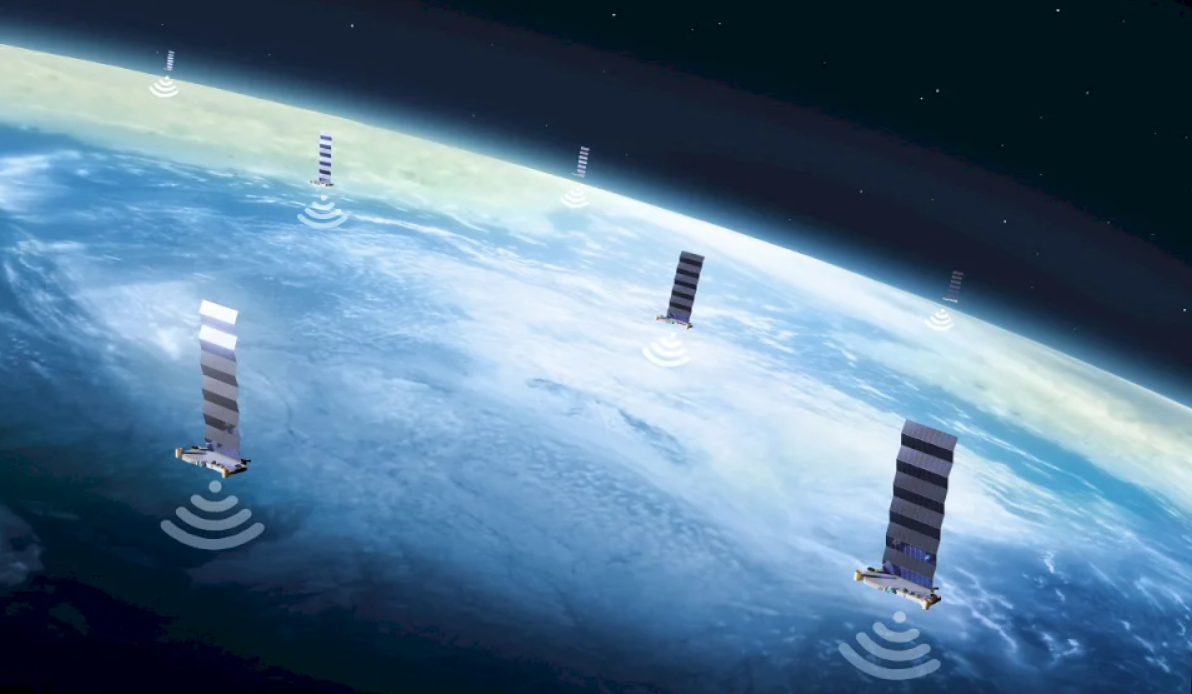

There are currently about 10,200 satellites operating in low Earth orbit, of which about 8,475 are Starlink satellites. In other words, nearly 80% of all satellites orbiting Earth belong to billionaire Elon Musk’s company.

The European Space Agency (ESA) predicts that the number of LEO satellites could increase to 100,000 by 2030, mainly thanks to SpaceX, which is seeking permission to expand its network to 42,000 satellites. In addition, competitors such as billionaire Jeff Bezos’ Kuiper (3,200 satellites) or the two Chinese networks GuoWang and Qianfan (18,000 satellites in total) will also contribute to this satellite storm.

Designed to “fall”

Each Starlink satellite has a lifespan of about five years. They orbit Earth at speeds of more than 27,000 km/h. At this altitude, the satellites are still affected by about 95% of Earth’s gravity, but drag from the thin atmosphere gradually slows them down.

To maintain orbit, Starlink uses krypton or argon engines to propel itself upward. When the fuel runs out, the satellite loses its ability to self-right and gradually falls back to Earth.

Before that happens, SpaceX often actively steers satellites into a controlled fall, aiming for open ocean instead of random re-entry.

Worrying problem

Physicist McDowell said — and SpaceX acknowledged — some satellites will not burn up completely upon re-entry, despite being designed to do so.

“They [SpaceX] say the satellites are designed to burn up completely. But in reality, it may not be that way – most of it will melt, but there will still be some left,” he said.

In the past, Earth has witnessed many pieces of space debris falling to Earth – from the US Skylab space station, the Soviet Salyut 7, the Russian Kosmos 2251 satellite or parts of the European Ariane 5 rocket. Even SpaceX’s Crew-9 Dragon spacecraft has left “space junk” falling to Earth.

But the sheer scale of Starlink makes this threat different. If one Starlink satellite collides with another, it could trigger a “Kessler effect” – a chain reaction of debris crashing into each other, destroying the entire satellite system in operation. This is the scenario that the movie “Gravity” simulated.

A single impact could cripple global GPS, telecommunications, financial, and weather forecasting systems. In the worst-case scenario, modern civilization could fall into chaos.

McDowell warned that the rate at which Starlink satellites are falling to Earth is just the beginning. When the first generation expires, SpaceX will send 4–5 satellites down in controlled crashes every day. That number will continue to increase as tens of thousands of new satellites reach retirement age. The result could be a constant “toxic metal fireworks display” in the atmosphere, sometimes even falling to the ground.

Commitment to “burn down completely” and the reality is far different

In July 2024, SpaceX told regulators that Starlink satellites were designed to “burn up completely” when they fell. But just eight months later, New Scientist magazine reported that a 2.5 kg piece of aluminum from a Starlink satellite had fallen onto a farm in Saskatchewan, Canada. SpaceX was forced to admit that it was a piece of the module’s lid, which was supposed to burn up in the atmosphere.

In January 2025, a “fireball” streaked across the Chicago sky, identified by McDowell as Starlink-5693 – a satellite that crashed uncontrollably due to a technical error. Starlink’s vice president of engineering, Michael Nicolls, confirmed that it was a “loss of direction” incident, but assured that most of the satellites burned up upon re-entry.

Leave a Reply