A post labeled “SAD K-POP NEWS” exploded across feeds claiming “The Dark Prodigy” died at thirty, and within minutes the internet reacted like a stadium losing power, because people fear celebrity death the way they fear sudden silence.

No official name was attached, yet the caption felt specific enough to trigger panic, because it promised a tragedy and a revelation, and revelations are the currency that keeps fan communities refreshing the page even when the truth is unclear.

Then came the second hook: a shocking private letter, supposedly revealed after his death, said to expose deep wounds and a turbulent life, and that promise turned sadness into obsession because pain feels like proof of authenticity.

Fans shared it fast, some out of love, some out of fear, and some out of adrenaline, because getting there first feels like loyalty online, even though speed often becomes the enemy of care and the ally of rumor.

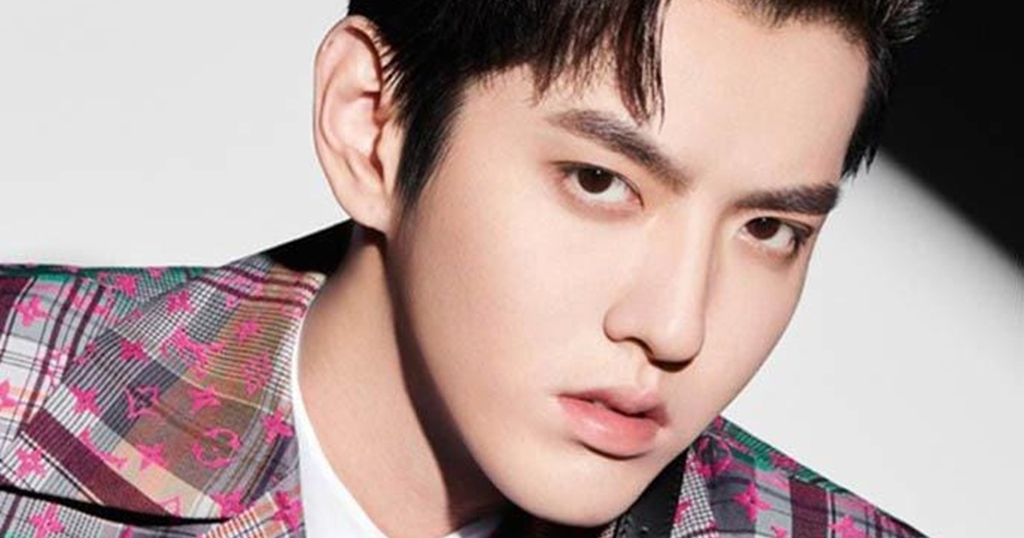

In this fictional telling, “The Dark Prodigy” wasn’t famous only for talent, but for intensity, the kind that makes a performer seem larger than life while quietly shrinking the person behind the stage lights.

He had a voice that could sound like velvet and break like glass, and he carried a public image built from mystery, eyeliner, and discipline, as if darkness were a brand rather than a wound.

People loved the aesthetic because it felt honest, but aesthetics can also become armor, and armor can trap you, because when the audience expects you to be broken beautifully, healing becomes a betrayal of the role.

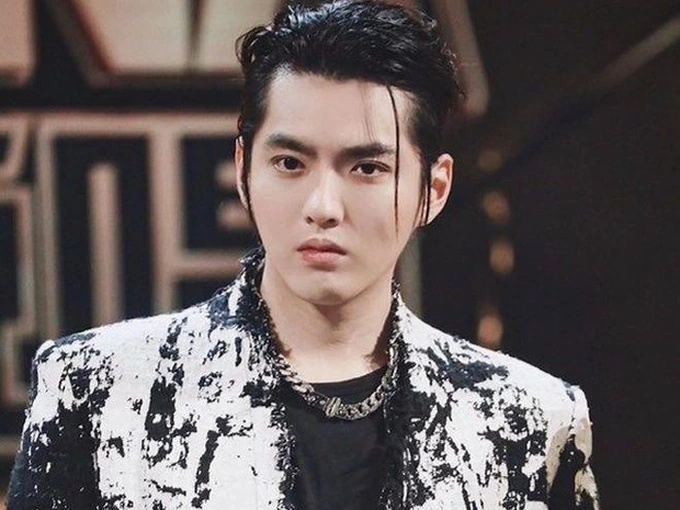

The rumors said he worked impossibly hard, sleeping in studios, re-recording lines until sunrise, apologizing for mistakes that nobody else noticed, and treating exhaustion like a debt he owed to every person who believed in him.

At thirty, the caption claimed he “passed away,” but the story didn’t explain how, which made the speculation uglier, because unclear death invites strangers to diagnose, blame, and invent conspiracies that feel like comfort to them.

The “private letter” was described as heartbreaking, and the narration claimed it revealed his deepest wounds, yet that framing is itself controversial, because when a person dies, their privacy usually becomes a battleground.

Some fans argued the letter was a gift, a final conversation, proof that he trusted them, while others said publishing it was exploitation, turning a human being’s last vulnerable words into content designed for engagement.

In the fictional letter, he wrote about smiling onstage while fighting panic backstage, about eating alone after award shows, and about feeling like love from millions still couldn’t reach the lonely places inside his chest.

He wrote that fame amplified everything, including shame, because one mistake became a headline and one rumor became a mountain, and he felt trapped between perfection demanded by the industry and perfection demanded by himself.

He described how people praised his darkness, but no one asked whether the darkness was safe, and that line hit fans hardest, because it forced them to consider whether their admiration ever turned into pressure.

Online, people reacted in predictable waves: grief posts, tribute videos, edits with sad music, and threads accusing someone, because modern mourning often looks like content creation, especially when the algorithm rewards strong emotion.

Some blamed the industry, calling it a machine that eats young talent, while others blamed “toxic fans,” and others blamed mental health stigma, because blame feels like action when you cannot undo what happened.

A smaller group insisted the letter was fake, created for clicks, because the internet has trained people to distrust even tenderness, and when you can’t verify, suspicion becomes the default defense mechanism.

Then the debate shifted to a darker question: even if the letter were real, did anyone have the right to publish it, and if not, how did it leak, and who profited from turning private pain into public spectacle.

This is where the story becomes a mirror, because the same people who claim to love an artist also demand access to their suffering, and the demand can be framed as “care” while still invading boundaries.

In the fictional timeline, fans began searching old interviews for “signs,” quoting moments out of context, building a retroactive tragedy, because humans hate randomness and will rewrite history to make it feel inevitable.

But inevitability is a trap, because it can normalize despair, and it can convince people that intense artists are “destined” to die, which romanticizes suffering and makes self-destruction seem like part of the brand.

As tributes multiplied, so did monetization, because tragedy drives traffic, traffic drives money, and money drives more tragedy posts, until grief becomes a marketplace where sincerity competes with opportunism in the same feed.

Some fans tried to do something different, organizing charity donations and mental health resources, insisting that honoring his memory meant protecting the living, not only worshiping the dead, and that shift felt like real maturity.

Others pushed back, saying the focus should stay on him, not on broader issues, revealing a painful truth: communities can love a person and still resist changing the behaviors that harmed them.

The fictional “Dark Prodigy” wrote one line that became the most quoted, not because it was the most poetic, but because it sounded like a plea: that people stop confusing performance with wellbeing.

He wrote that he could make pain look beautiful, but making pain look beautiful didn’t make it safe, and that sentence broke fans open because it indicted the entire culture of aesthetic suffering.

His letter also criticized himself, accusing his own mind of being a stricter manager than any company executive, which sparked debate about where responsibility truly rests in a world that rewards perfection relentlessly.

If you treat the industry as the only villain, you miss the role of audience appetite, yet if you treat fans as the only villain, you ignore structure, contracts, and the brutal economics of attention.

The most honest conclusion is that pressure is distributed, and that’s exactly why it persists, because everyone can point somewhere else and say, “It wasn’t me,” while still participating in the machine.

In this kind of story, the “shocking letter” becomes a symbol, and symbols are dangerous, because they can educate people or they can be weaponized, depending on whether the community chooses empathy or spectacle.

If you share a death post, you can share it with restraint, avoiding speculation and blaming, and focusing on verified information and compassion, because rumor-mourning can become harassment within hours.

If you share a private letter, you can ask whether it was meant for you, whether it respects dignity, and whether your curiosity is helping anyone, because curiosity without consent can harm even when it wears a sad face.

The “Dark Prodigy” myth would be easy to romanticize, yet romanticizing it teaches the next generation that suffering is the price of greatness, and that lesson is not art, it’s a quiet form of violence.

So the real shock isn’t only the letter, but the way the world responds, because the internet can turn a human being into a trending topic in minutes, and a trending topic rarely receives the gentleness a human deserves.

If this story leaves you unsettled, let it, because discomfort is where change starts, and the most meaningful tribute to any struggling artist is a culture that values wellness the moment the music stops.

Leave a Reply