The 1947 Disappearing Miners: A 73-Year Ghost Story Rewritten by One Recent Discovery”

For seventy-three years, the mystery of the miners who vanished in 1947 has haunted the history of mining like a stubborn ghost, a tragedy that left families with no answers and a town with a wound that never quite closed.

The official story was simple, almost merciful in its bluntness: a sudden collapse, an instant death, bodies sealed forever in the choking dark, fate locked behind rock and rubble.

It was the kind of explanation people accept not because it feels true, but because it allows them to sleep, because uncertainty is heavier than grief and harder to carry through generations.

The mine was eventually quieted, the entrance reinforced, the paperwork filed, and the names of the missing men were carved into memorial plaques that tried to substitute for a goodbye.

Wives raised children who grew up with the same unfinished question, and those children grew old before the question ever softened: how do people disappear without leaving even a final trace.

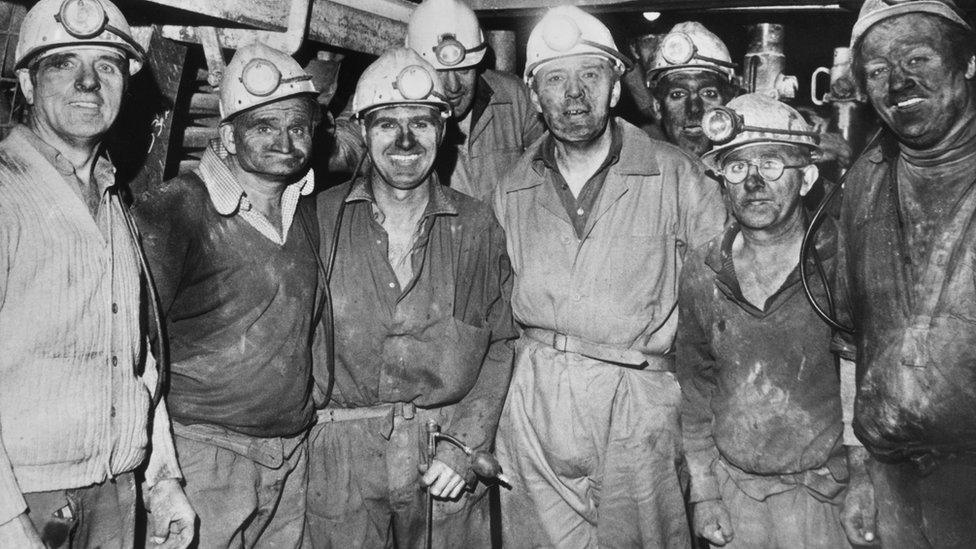

In 1947, the mine had been the community’s heartbeat, a deep industrial artery that fed the town with wages, pride, and a dangerous sense of normalcy.

Men went down before dawn, lanterns swaying, lunch pails knocking against thighs, trading jokes as if laughter could bargain with the underground.

They called it “the belly of the mountain,” and the mountain always listened, patient, silent, and in the end, unforgiving.

The day of the collapse began like any other, the kind of day you don’t remember because nothing announces itself as historic until it’s already too late.

There was a dull tremor underground, then the violent sound of stone shifting, and within minutes, a section failed, swallowing equipment, air, and men in one brutal inhale.

Rescue crews descended immediately, choking on dust, forcing themselves into tight corridors with the stubborn bravery of people who can’t accept that the earth has already made its decision.

For days they dug, hammered, braced timbers, listened for tapping, for a shout, for anything that could prove the missing miners weren’t already gone.

But the mine gave them nothing—no voices, no knocking, no signs of a pocket of air—and the deeper they went, the more unstable everything became.

Officials eventually declared the search too dangerous, and the words used to justify the withdrawal were careful, polished, and cold: “No survivable conditions.”

Families were told the men had died instantly, as if instant death were a gift, as if it were easier to picture a sudden end than to imagine slow darkness.

The town held a funeral without coffins, a ceremony built from prayers and empty space, and the mine entrance became a sealed scar on the hillside.

Over time, rumors grew where facts had failed, because when a story doesn’t have an ending, people invent one to stop the mind from looping forever.

Some swore they saw lights near the closed shaft at night, others claimed they heard faint tapping when the wind fell quiet, and children dared each other to stand near the warning signs.

The missing miners became more than victims; they became folklore, a local myth stitched together from grief and the human need for a narrative.

Then, decades later, the world changed, the town shrank, and the mine shifted from a working site into an abandoned relic guarded by fences and old fear.

For most people, it would have stayed that way—until a recent discovery reopened the story in the most unsettling way possible.

It started with a modern survey, the kind that happens when companies evaluate old sites for stability, groundwater risk, or potential redevelopment.

Engineers used new imaging techniques to map voids and collapsed pathways far beyond what 1947 technology could see, turning the mountain into a ghostly blueprint.

One scan showed something that made the team pause: a cavity that shouldn’t have existed, a pocket formed behind a fallen wall, sealed off like a room the mine never meant to build.

At first, they assumed it was a natural void, a fluke of geology, but the shape was wrong—too defined, too organized, too much like a place people had used.

When the team cross-referenced old maps, they realized the cavity sat near the section where the missing crew had last been recorded working, a location that should have been inaccessible after the collapse.

That realization triggered a careful excavation plan, not a dramatic dig, but a slow, methodical opening designed to avoid reigniting instability in a mountain with a long memory.

The work took weeks, and each foot of debris removed felt like pulling at the seam of a shroud that had covered the truth for generations.

Then, finally, a narrow opening appeared, and cold, stale air breathed out from the blackness as if the mine itself were exhaling after decades of holding its secret.

A camera was fed through first, because no one wanted a second tragedy, and the monitors showed a cramped space coated in dust and time.

At the edge of the frame, something pale caught the light—fabric, or paper, or the ghost of something human-made in a place that should have been empty.

When the opening was widened enough for an investigator to crawl through, the discovery stopped being an abstract mystery and became a scene that twisted the stomach.

Inside the pocket was a makeshift shelter: stacked boards, remnants of cloth, and what looked like deliberate arrangement rather than random collapse.

There were personal items too—lunch pails, a dented canteen, a metal tag—and on the ground, scratches in the dust that were unmistakably not made by falling stone.

They were marks made by hands, by human effort, by someone trying to communicate or count or survive.

The most haunting part wasn’t the artifacts; it was the evidence of time—evidence that suggested the men did not die instantly.

A wall held a series of tally marks, uneven and desperate, as if someone had been tracking days or hours while the outside world decided silence meant death.

Nearby, etched into a beam with something sharp, were letters that formed partial names, the kind of crude carving made by someone who needed proof he had existed.

The investigators found a small tin box wrapped in cloth, protected like a final treasure, and inside it were papers fused together by moisture and years.

They were unreadable at first glance, but the edges showed ink, and that ink meant someone had written something down in the darkness, believing words could outlive stone.

When the documents were later stabilized and examined, the content—what could be recovered—rewrote the town’s tragedy in a way that made the old official narrative feel like an insult.

Because those fragments spoke not of instant death, but of survival—short, brutal, courageous survival behind a wall the rescuers never breached.

The recovered notes described the initial collapse, the scramble to find air, the realization that the main tunnel had been sealed, and the decision to move into a pocket they believed might connect to another passage.

They wrote about rationing matches, sharing water by capfuls, and listening for sounds that never came close enough to promise rescue.

Leave a Reply