For years, Canada’s fighter jet story seemed pre-written. Washington would nudge, American defense giants would lobby, and Ottawa would eventually sign on the dotted line for a U.S.-built aircraft that served broader American strategic interests as much as, if not more than, Canada’s own.

This time, something is different.

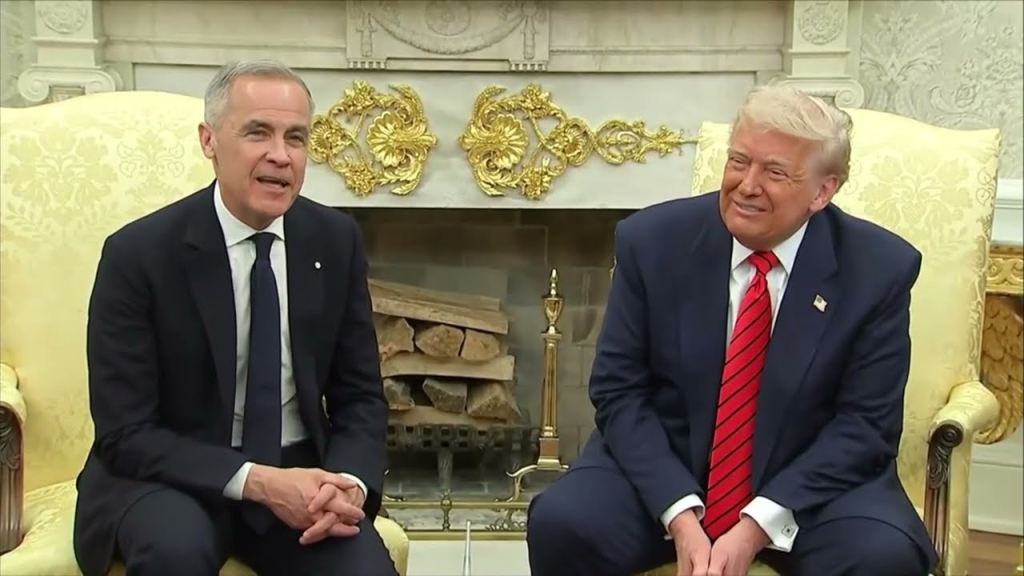

Behind closed doors, a quiet but profound shift is underway. Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government has ordered a hard review of Canada’s F-35 contract with Lockheed Martin, and in the shadows of that reassessment, another name has surged from “outsider” to serious contender: Sweden’s Saab Gripen.

On paper, it’s a competition over 88 fighter jets. In reality, it’s a referendum on who controls Canada’s future — Canada itself, or the American defense machine.

Inside Ottawa, the atmosphere has changed from routine procurement to long-term strategy session. Engineers, pilots, and defense planners are not thinking in four-year terms or election cycles. They are thinking in fifty. Arctic patrols in blinding blizzards. Northern sovereignty missions from remote, icy strips. Continental defense under NORAD. Long, lonely stretches of airspace where support is thin and failure is unforgiving.

In that context, the Gripen stops looking like a quirky European alternative and starts looking like it was built for Canada.

The Swedish jet is optimized for tough-weather nations with huge territory and limited support infrastructure. It can launch from short, rough runways — the kind carved out of frozen northern strips. It is designed to work in bitter, sub-zero climates. It can be turned around quickly with small ground crews. Its operating costs are dramatically lower than heavy, maintenance-hungry platforms.

But the real shock is not what the Gripen can do in the air. It’s what it offers on the ground: control.

Under a Gripen partnership, Canada would not just be a customer; it could be a co-creator. Sweden has put forward a package that goes far beyond a simple purchase: shared development, shared engineering, local assembly, deep technology transfer, and major industrial investment. Rolls-Royce is at the table with proposals to bring engine production, research programs, and aerospace innovation directly into Canadian hubs like Montreal and Winnipeg.

It isn’t just jets. It’s a chance to rebuild a national aerospace identity that many Canadians still mourn, ever since the Avro Arrow was killed and a generation of talent was scattered. For those who know that history, the number “88” carries emotional weight. These aircraft would not just patrol the Arctic — they would symbolize that Canada is done outsourcing its destiny.

Meanwhile, the F-35 — for all its raw capability — comes with fine print. Switzerland’s internal evaluation, quietly shared among allies, raised red flags: lifetime costs far higher than advertised, extreme maintenance demands, strict software and upgrade controls, and deep dependence on U.S. systems for mission planning, weapons integration, and even operational flexibility.

In blunt terms: you get the jet, but Washington keeps the keys.

Canada’s geography and politics make that trade-off harder to swallow than ever. The Arctic is now a contested frontier. Russia is ramping up its presence. China is probing Pacific routes. Finland and Sweden have joined NATO, aligning northern defense interests in a way that suddenly makes a Nordic–Canadian air power bloc very real. These nations share brutal winters, remote bases, long borders — and a strong instinct for strategic independence.

It’s no accident that as all of this unfolded, Swedish export reports began hinting at a major North American partner in their Gripen pipeline. Technical delegations shuttled quietly between Ottawa and Stockholm. Rolls-Royce deepened its involvement. Senior Swedish officials began dropping guarded remarks about a Western ally leaning favorably toward Gripen.

From the outside, it looks like silence. Inside Ottawa, it looks like preparation — and protection.

Because the moment Canada publicly signals a tilt toward Gripen, the blowback will be intense. Washington has enormous leverage over Canadian defense policy. The F-35 program is backed by powerful lobbyists, entrenched institutions, and a long tradition of Canada playing the junior partner. If Ottawa makes a sovereign choice that breaks that pattern, every pressure point will be tested.

That’s why the process has stayed so guarded: not to hide from Canadians, but to shield the decision until the government is ready to stand behind it.

Early indicators from within the system are striking. Arctic compatibility studies give the Gripen a clear edge. Operating cost simulations show major long-term savings. Industrial partnership frameworks are being drafted, not just in theory but with concrete roles for Canadian firms. Rolls-Royce proposals would inject fresh energy into an aerospace sector that has waited decades for a genuinely national project.

If Canada chooses the Gripen, it would not just be choosing a fighter. It would be choosing a new posture: from follower to builder, from dependent to autonomous, from default U.S. platform to an alliance of equals with northern partners who share our climate, our constraints, and our desire to stand on our own feet.

Those 88 jets would become more than silhouettes in the northern sky. They would be a message — to allies, adversaries, and Canadians themselves — that this country is done sleepwalking through its defense choices.

This is not dithering. It is discipline. It is the sound of Canada thinking like a sovereign nation again. And when the decision is finally announced, the world will understand that the quiet wasn’t indecision. It was Canada, for once, refusing to be told what to buy — and deciding, instead, who it wants to be.

Leave a Reply