There is a quiet earthquake shaking North America’s auto industry, and almost nobody in Washington wants to talk about it.

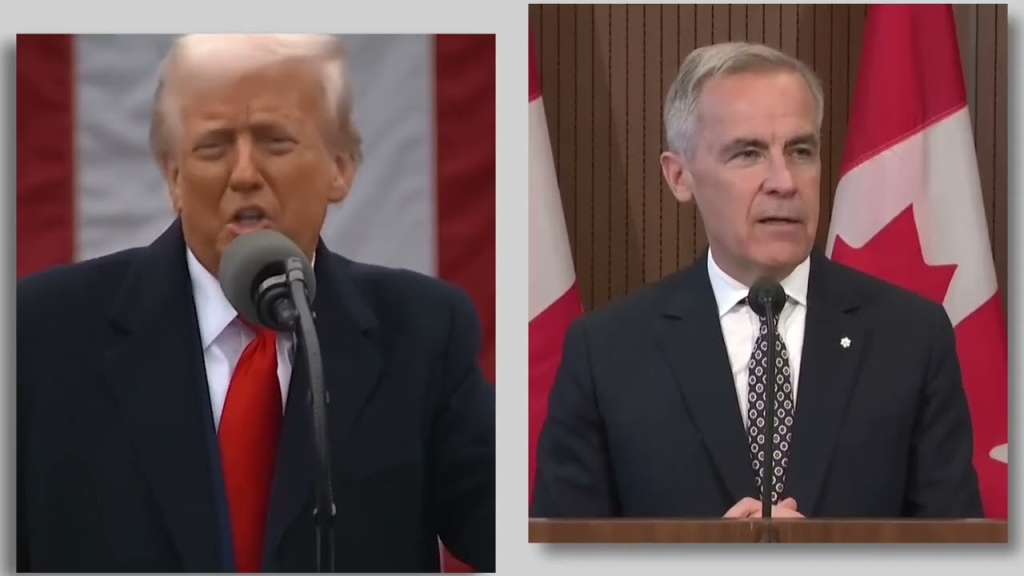

For decades, Japanese automakers treated the United States as their crown jewel market — a place where long-term partnerships, stable rules, and predictable policy made massive investments worth the risk. But that era is fading fast. Under Donald Trump’s aggressive tariff regime, the careful balance that once tied Japan’s car giants to American factories and consumers is breaking apart.

And the country that’s cashing in on the chaos isn’t China or Mexico.

It’s Canada.

The shift didn’t start with a dramatic press conference or a viral protest. It began with one decision that insiders immediately recognized as a red flag. In early 2025, Subaru announced that its plant in Lafayette, Indiana, would stop producing the Outback for the Canadian market. That’s not some niche model — the Outback is Subaru’s top seller in North America.

Instead of building those vehicles in the U.S. and shipping them to Canada as usual, Subaru will now make Canadian Outbacks back home in Gunma, Japan. Why? Because Canada and Japan have a free trade agreement that keeps tariffs at zero, while U.S. policy has turned every cross-border shipment into a financial minefield.

Within a single year, imports from the U.S. to Canada plunged from 26% to just 10%. Stacked tariffs — 25% from the U.S., 25% from Canada — turned cross-border production into a losing game. The supply chain that once made perfect sense under NAFTA-style assumptions now looks suicidal on a balance sheet.

And Subaru isn’t alone.

Japan’s auto industry is one of the pillars of its economy. More than a quarter of its exported vehicles head to the United States. Around 8% of Japan’s workforce is tied to the sector. Now, thanks to Trump-era tariffs, cars built in Japan for the U.S. can face effective charges approaching 49%. Global suppliers describe the situation as a war of attrition: survival isn’t about innovation anymore, it’s about having enough cash to outlast bad policy.

The pressure has triggered something unprecedented in years: a geographic reshuffling of where Japanese automakers choose to base their long-term North American operations.

Subaru’s move was an early warning shot. Soon after, other giants began quietly adjusting their plans. Toyota, Honda, Mazda, Mitsubishi — instead of doubling down on the United States, they started redirecting more of their capacity, research, logistics, and management functions to Canada.

Behind their corporate language is a simple calculation:

Canada offers stability, the U.S. offers volatility.

Analysts estimate Japanese automakers are losing nearly $25 billion per year from these tariff battles. Toyota alone carries a massive share of that hit. At those levels, nostalgia for the American market doesn’t matter. Math does.

Ontario, with its existing plants, established suppliers, and trade agreements, suddenly looks like safe harbor. While American consumers brace for higher prices on everything from new vehicles to basic parts like brake pads, filters, and tires, Canada is positioning itself as the new central hub for Japanese-brand production.

Toyota and Honda are expanding hybrid and EV capacity inside Canada. Smaller Japanese firms are shifting research labs and analytics teams to Toronto, turning the city into a command center for export oversight and supply chain strategy. They want to stay plugged into Asia, reach global markets, and still serve North America — without being trapped inside Washington’s tariff crossfire.

Some economists are blunt: this may be the most important but least discussed economic story of 2025.

In automotive towns across Ontario — Aliston, Cambridge, and others — the momentum feels familiar. Residents remember the 1980s, when Reagan-era restrictions on Japanese imports pushed Honda and Toyota to build plants in Canada. Those decisions revived local economies and turned Canada into an unexpected manufacturing powerhouse for vehicles headed straight into the U.S. market.

History is repeating itself, but with much higher stakes.

Today’s supply chains aren’t just about steel and engines. They rely on advanced electronics, electric drivetrains, and fragile global networks. That kind of system can’t survive repeated policy shockwaves. It needs one thing above all else: predictability.

Canada offers it.

Seven Japanese auto plants already operate there: five building light vehicles, one producing engines, and one making trucks. They support around 30,000 direct jobs and many more indirectly. Over $14 billion in Japanese auto investment has flowed into Canada so far. Since 1993, more than 5.2 million Japanese-brand vehicles built in Canada have been shipped around the world. Canada isn’t just assembling cars — it’s become a launchpad.

Trump’s tariffs were supposed to “bring manufacturing back” to the United States. Instead, the cumulative effect of charges on steel, aluminum, parts, and finished vehicles is making American-made cars more expensive and less competitive. Fusion TG estimates that when multiple tariffs stack on a single vehicle, the final sticker price can more than double by the time it reaches U.S. buyers.

Global companies can’t absorb that forever. So they’re adopting a new survival model:

high-value design and engineering in Japan, mass production in Canada, exports to the world.

Canada’s trade agreements — including frameworks like CPTPP — allow Japanese cars to enter tariff-free, then ship out again to global markets. Every time Washington escalates tariffs, Canada’s relative advantage grows.

And Japanese automakers aren’t the only ones noticing. European and South Korean car companies are starting to copy the playbook: move operations, expand logistics, and set up development centers in Canada to keep access to North American customers without stepping into the tariff war zone.

Trump wanted to rebuild American manufacturing dominance. Instead, his tariff storm may be remembered as the moment Canada quietly became the new heart of the Japanese auto empire in North America — while the U.S. watched its leverage drive right across the border.

Leave a Reply